Last week Websense published a post 3-2-1 WordPress vulnerability leads to possible new exploit kit written by Stephan Chenette their Principal Security Researcher, which made a the claim that there were publicly available vulnerabilities for WordPress 3.2.1 and that a malware infection was hitting only WordPress 3.2.1 based websites. Their post lead to articles in SC Magazine and PC World repeating the claims.

Previously we discussed the fact that the claimed “publicly available exploits” did not actually exist. It’s worth taking a more in depth look at that claim because if there were standards for security researchers than Websense’s Principal Security Researcher would likely have been grossly negligent in this situation.

After our previous post we were still curious with the possibility that there might be a vulnerability in WordPress 3.2.1 based on their claim that all the websites with this particular infection were running WordPress 3.2.1. We looked into this and have found that this is also false. Our finding on that also raises serious questions as to how their researcher could have come to have that conclusion.

What Stephan Chenette and Websense have done by making these baseless claims is highly inappropriate. It is a serious charge to make that software, even if it is an out of date version, has such a serious security vulnerability. To do that based on such blatantly incorrect information and with a complete lack of due diligence is inexcusable and should lead to repercussions for everyone involved in creating and spreading these falsehoods.

Publicly Available Exploits for WordPress 3.2.1?

In the post Chenette said that “Based on my analysis, the site was compromised because it was running an old version of WordPress (3.2.1) that is vulnerable to publicly available exploits [1] [2].”.

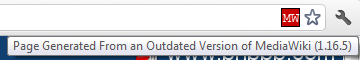

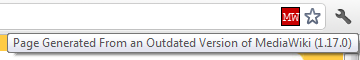

The exploits Chenette is citing come from Exploit Database. That website and other similar websites that list claimed vulnerabilities in software include submissions that have not been verified to be actually exploits before being published. Exploit Database includes vulnerability reports that are completely false, like this submission that claimed that the WordPress plugin WP Touch contained a vulnerability in a file despite the fact that the file that doesn’t even exist in the plugin. Anyone serious about security research would verify the vulnerability found on one these websites actually exists before citing it. Those reports also shouldn’t be cited by news organizations unless this has been done.

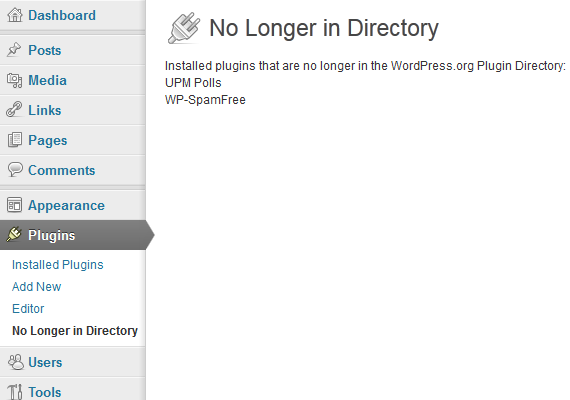

We know that Chenette didn’t verify these vulnerabilities because if he had attempted to verify the vulnerabilities he would have seen that vulnerabilities mentioned were not in WordPress 3.2.1 or WordPress at all. Instead these vulnerabilities where for WordPress plugins WP-SpamFree and UPM-POLLS. He would have also known if he had just looked at the titles of the exploit reports, which are “WP-SpamFree WordPress Spam Plugin SQL Injection Vulnerability” and “Wordpress UPM-POLLS Plugin 1.0.4 Blind SQL Injection”. What it looks he did was to do a search for WordPress 3.2.1 for that website and just grabbed those results without bothering to look at what they were. If this is level of research Websense’s Principal Security Researcher does, we would hate to see what the subordinates are doing.

There is no evidence that those plugins were exploited on the infected websites and when we checked a few of the websites that we were listed in the Websense post the plugins didn’t even appear to on the websites. In any case because the vulnerabilities are in plugins, if you had plugin installed that was exploitable you would be just a vulnerable whether you were running WordPress 3.2.1, WordPress 3.3.1, or another version.

All The Websites Running WordPress 3.2.1?

The post claimed that all the websites with this infection were running WordPress 3.2.1. If this were true it could be an indication that the infection of the websites was due to an exploit of something specific to WordPress 3.2.1, even though the claimed publicly available exploits did not exist.

As we mentioned in the previous post there are a number of possible explanations why all the infected websites would be running WordPress 3.2.1 without there being an exploit of something in WordPress 3.2.1.

The other possibility is that Websense post was incorrect in claiming all the website were running WordPress 3.2.1. In our previous post we found that for the other claim of a WordPress 3.2.1 vulnerability, by M86 Security Labs, the sample list of infected websites did not contain only websites recently running WordPress 3.2.1 as claimed. In Websense’s case we found that the sample list of 11 websites, included with their post, to have all been running WordPress 3.2.1 recently.

Because the possibility of a remotely exploitable vulnerability in WordPress 3.2.1 is such a serious issue we wanted to look further into the possibility that this infection was in fact due to an exploit of WordPress 3.2.1 as implicated by Websense’s post. The best way to check for this would be to review the HTTP log of an infected website. If an exploit of WordPress 3.2.1 had been the cause that should be discernible in the log. So far we have not cleaned up any websites with this infection, so we haven’t had a chance to do that.

If we could find websites running an earlier version of WordPress (if a website is running a new version it could have been upgraded after the exploit) or not running WordPress at all then that would mean the infection is not limited to WordPress 3.2.1 and likely point to the infection having nothing to do with an exploit of WordPress 3.2.1.

To find websites that contained this infection we looked at Google’s Safe Browsing Diagnostic data. This data includes a few example of website they have found to contain a certain infection. We started with the data for the domain listed in Websense’s post . Two of those domains were now running WordPress 3.3.1. The third doesn’t appear to run WordPress, but it was down so we couldn’t confirm if it contained the malware. We then look at the reports for three more domains involved.

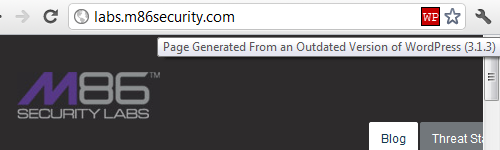

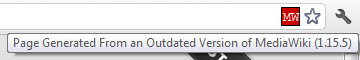

Of the 11 websites that we checked, that appear to had been infected with the malware based on Google’s data, we found 2 were currently infected with the malware and were not running WordPress 3.2.1 or above. We found http://www.weightloss-blogs.org/ which was running WordPress 3.1.3 and contained the malware at the time we checked. This shows that the exploit could not be something specific to WordPress 3.2.1. We also found http://victoryaog.org/joomla/, which as you might guess from the URL is running Joomla instead of WordPress and contained the malware at the time we checked. This shows that it is not something specific to WordPress. We found more that were not running WordPress at all, but were not currently infected so we can’t be totally sure they were infected. Our results show that Websense’s claim that this is infection is specific to websites running WordPress 3.2.1 be baseless.

That finding also raises questions about their data. How could they have found 100+ websites, including the sample list of 11 websites, all running WordPress 3.2.1 but with a much sample set of only 11 we found 2 confirmed instances where this wasn’t the case? They are a few possibilities we could think of.

One possibility is that their data is not very representative of the Internet as a whole, which would make the data unreliable for research purposes and make any reports based on it unreliable as well.

Another possibility is that their system for reviewing their data is flawed or the person doing the analysis screwed up. Maybe they only looked for websites running WordPress 3.2.1, in which case obviously all the infected websites they looked at would be running WordPress 3.2.1. WordPress powers many websites, so finding 100+ that were infected wouldn’t be surprising.

The most troubling possibility, and we need to emphasize that we don’t have any evidence of this, is that their data didn’t actually show that all the website were running WordPress 3.2.1 and they intentionally created a sample list of websites that only contained websites running WordPress 3.2.1.